Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Europe needs an “emergency mindset” on deterrence and defence if it is to survive a global disorder where strength matters above all, Denmark’s prime minister has warned.

Mette Frederiksen, who has been thrust by the Greenland crisis to the centre of a rupturing transatlantic alliance, told the FT that “a Europe that is not able and willing to protect itself is going to die at some point”.

“The old world will not come back. I am pretty sure about that,” she added. “Unfortunately, strength is one of the weapons that is useful in this new world disorder and therefore Europe has to be strong enough.”

Donald Trump’s threat to take control of Greenland from Nato ally Denmark last month threw the eight-decade alliance into disarray. Although the US president retreated from his demand for outright conquest, Frederiksen said the crisis had not been resolved.

“We will try to see if we can find a solution . . . but I don’t think it’s over,” she said in an interview at the Munich Security Conference.

Trump last month dropped his most extreme demands on the Arctic island after a meeting with Nato secretary-general Mark Rutte at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

A possible compromise involving a renegotiation of a 1951 treaty governing US military deployments in Greenland is being explored by a working group involving Danish, Greenlandic and US officials.

“Now we have a more traditional political diplomatic way forward,” said Frederiksen, who is due to meet US secretary of state Marco Rubio in Munich.

“We understand that for the US there are domestic defence issues when it comes to Greenland. That has always been the case and we will discuss that,” she said, reiterating that Denmark’s “red lines” on sovereignty would not be crossed.

The Greenland crisis has accelerated efforts by European capitals to reduce their defence reliance on the US, amid fear that Trump is retreating from Washington’s long-standing security guarantees to the continent.

“We need a sense of emergency in Europe,” said Frederiksen, one of Europe’s most committed Atlanticists.

“I will never suggest something that would separate the US from Europe,” she added, “but if the US does something that separates us, or partly separates us, then of course my strongest advice for the rest of Europe is to fill in those gaps.”

“There are changes going on in the US,” she said. “And therefore, you also have to act. But we had to do it no matter.”

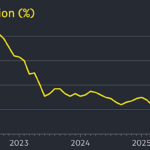

Denmark plans to spend 3.5 per cent of GDP on defence this year, as part of a cross-European surge in security spending agreed by Nato to appease Trump and seek to build a more sovereign European defence posture.

The Munich Security Conference has acted as the annual fête for the transatlantic alliance and litmus test of the state of US attitudes towards Europe. JD Vance, the US vice-president, last year shocked delegates with a scathing speech berating Europe.

European officials are nervously awaiting Rubio’s Saturday address, hoping for a more congenial tone.

But Frederiksen said relief or disappointment over single US comments or speeches should be resisted. “Both are the wrong way of acting, you have to look at the whole picture,” the 48-year-old prime minister said of the past eight decades of relative peace.

In a hint of nostalgia that is shared across the continent, she quipped: “I really enjoyed [the old world] by the way.”

Frederiksen praised her European and global allies for collectively standing up to Trump’s threats to Denmark and Greenland’s sovereignty. International pressure, market turmoil and domestic political resistance pushed Trump to back down.

“The unity tells us something: that the core ideas of a global world society — respect for sovereign states, territorial integrity and so on — are values that the majority in the world will not compromise on,” she said. “That has been extremely important.”

Frederiksen also defended the decision to deploy a small group of troops from European allies to Greenland during the crisis, which some US officials claimed was a provocation.

“It’s only positive that other Nato partners are present in the Kingdom of Denmark,” she said. “And by the way, we have been totally transparent about this with the Americans . . . they knew exactly what was going on and they knew why.”

Frederiksen, a two-term Social Democrat leader whose popularity has surged following the Greenland crisis ahead of an expected parliamentary election this year, said Nato would need to change to match the shifting US foreign policy under Trump.

“The world is changing, so Nato is changing as well. Of course, there will be discussions about Nato, but I think we have to do what we can to make it survive,” she said.