Two families, unconcerned with dignity. The Hathaways are farmers, in the English county of Warwickshire, with close ties to the land—some would say too close, at least in the case of Agnes, a young woman so eccentrically at one with nature that she is rumored to have been born of a forest witch. The Shakespeares are led by a glover, whose business has seen better days. His eldest son—William, of course, though he is not immediately identified as such—defrays his father’s debts by tutoring Agnes’s younger brothers in Latin, an arrangement that begets many reversals of fortune. Agnes and William fall in love; conceive a daughter, named Susanna; and marry, over the protests of their families. A few years later, Agnes bears twins, Hamnet and Judith, introducing a note of dread: Agnes’s dreams have shown two children, not three, standing at her deathbed. In more than one sense, the stage is set for tragedy.

What’s in a name? Plenty. At the beginning of “Hamnet,” a tempest of a movie from the director Chloé Zhao, we’re told that, in sixteenth-century England, the monikers Hamlet and Hamnet were used interchangeably. The premise of the film—and of Maggie O’Farrell’s novel of the same title, published in 2020—is that, after his son’s death, in 1596, Shakespeare wrote “Hamlet” in a burst of raw, unexpurgated grief. It’s a notion made for scholarly dispute: several other plays, including two comedies, “Much Ado About Nothing” and “As You Like It,” came between the death of Hamnet and the creation of “Hamlet.” Still, loss hews to no temporal logic but its own, and it would be foolish to hold O’Farrell’s unabashed historical fantasy to a persnickety standard. The more trenchant critique, surely, is that the entwining of art and life has become a tiresome conceit, predicated on the bland notion that all great fiction must have an autobiographical component and a therapeutic aim.

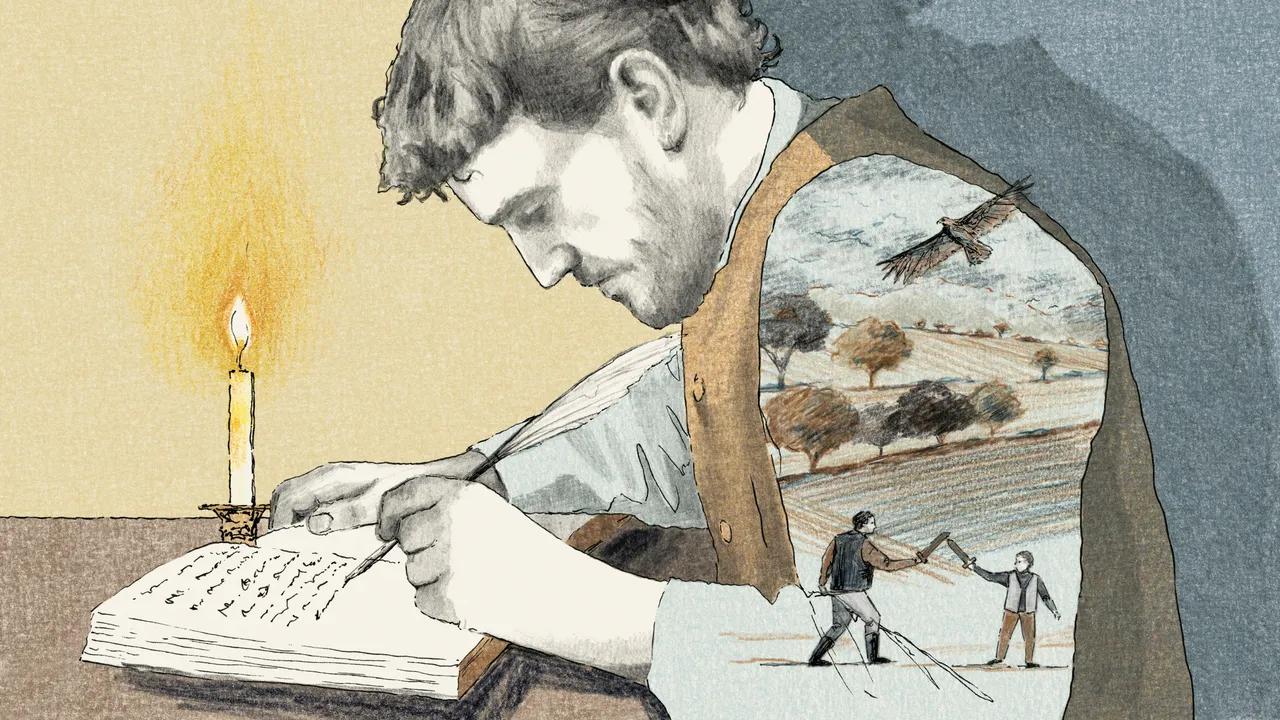

Zhao’s “Hamnet” does not exactly scrape the mold off these clichés, and that is fine and even fitting. If there be fungus of any kind, you can rest assured that the earthy Agnes (Jessie Buckley) will find a use for it. We first see her in a forest, curled up between the roots of a tree. Rising, she strides through the woods with a hawk on her arm and various mugwort-based remedies committed to memory. There has always been a native wildness to Buckley; in the psychological thriller “Beast” (2017), she was a creature of the Jersey coast, feral, urchinlike, perpetually smeared with mud. Here, she cuts a more serene woodland figure—pale of skin, dark of hair, and clad in rusty browns and reds. No wonder that, returning to her family’s farmhouse, she immediately transfixes William (Paul Mescal), the Latin tutor, who spies this vision of freedom and loveliness from an upstairs window and looks boxed in by comparison. Zhao emphasizes his entrapment, shooting him through glass—a studied choice, but one that contextualizes her interest in this particular story. Agnes, in her matter-of-fact harmony with the natural world, is like an Elizabethan ancestor of Zhao’s contemporary American protagonists: the melancholy Lakota horsemen of “Songs My Brothers Taught Me” (2016), a restless widow cast adrift in “Nomadland” (2020). The bookish William, meanwhile, is also recognizably a Zhao construct: as a new husband and father, struggling to write a play by candlelight, he is possessed by a stubborn sense of his vocation. No less than the gravely injured cowboy hero of “The Rider” (2017), brazenly chasing his rodeo dreams, William must do what he was born to do.

Our Far-Flung Correspondents: A Centenary Issue

Subscribers get full access. Read the issue »

Zhao’s first three features were steeped in documentary realism, shot with a sturdy, windswept lyricism and abounding in nonprofessional actors. Then came her fourth picture, the clunky Marvel comic-book epic “Eternals” (2021)—a noble but self-evident failure, in which she channelled the visual and spiritual reveries of Terrence Malick, a longtime influence, in a vain attempt to transcend superhero-movie conventions. “Hamnet” is, inevitably, an improvement, though not exactly a return to form. It marks an unstable new mode for Zhao, a weave of subdued pastoral realism and forceful, sometimes pushy emotionalism. The movie whispers poetic sublimities in your ear one minute and tosses its prestige ambitions in your face the next.

The whiplash is disorienting, but, somewhat paradoxically, the characters’ romantic upheaval provides its own center of gravity. You are propelled alongside them as Agnes, sensing William’s creative and professional frustrations, packs him off to London to follow his dreams, hastening the pair’s descent into marital discontent and parental grief. Buckley is every inch the requisite force of nature, heaving and sweating up a storm as Agnes wrenches her children into this world, and moving swiftly from anguish to rage—a drained, defeated anger—as one of those children is yanked back out of it. Buckley and Mescal, both Irish and both bountifully gifted, have done quieter, subtler work elsewhere, though I can’t say that their histrionics miss the mark. What is “Hamnet,” or “Hamlet,” without a little ham?

O’Farrell’s novel is subtitled “A Novel of the Plague.” Its most gripping, least typical chapter describes an outbreak in breathlessly suspenseful detail, tracking the contagion from Alexandria, where a shipworker has a fateful encounter with a monkey’s fleas, all the way to England and, eventually, the Shakespeares’ doorstep. It’s no surprise that the film dispenses with this; its focus is on the domestic claustrophobia that William escapes and Agnes sacrificially endures. Agnes finds some comfort from her supportive brother Bartholomew (Joe Alwyn) and, in time, her mother-in-law, Mary (Emily Watson), who initially disapproves of Agnes but comes around to a grudging respect, rooted in shared experiences of drudgery and loss. This is Zhao’s first collaboration with the Polish cinematographer Łukasz Żal, who, in the Holocaust drama “The Zone of Interest” (2023), used an array of small hidden cameras to suggest the daily, routinized horrors of a Nazi family. “Hamnet” attempts nothing so technically virtuosic or historically queasy, and yet a not dissimilar air of home surveillance persists. Indoors, the Shakespeares are often shot unnaturally head on or in high-angled panoramas that diminish their stature. We could be studying them under glass.

Such intensity of focus may also explain why Zhao and O’Farrell have jettisoned the novel’s nonsequential narrative structure, which shuttles, quite intricately, between two parallel time frames. The film, by contrast, moves cleanly from start to finish, forgoing any impulse toward Malickian nonlinearity. Even so, Zhao remains vividly under the spell of Malick the image-maker, and also Malick the intimate observer of the everyday. She has a great eye for sunlight, especially when filtered through a woodsy canopy of green, and in the family’s happier moments she’s exquisitely attentive to the joyful chaos of Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) and Judith (Olivia Lynes) at play. At one point, the kids pretend to be the Weird Sisters. Their father may be a fitful presence at home, but his work already has them under its spell.