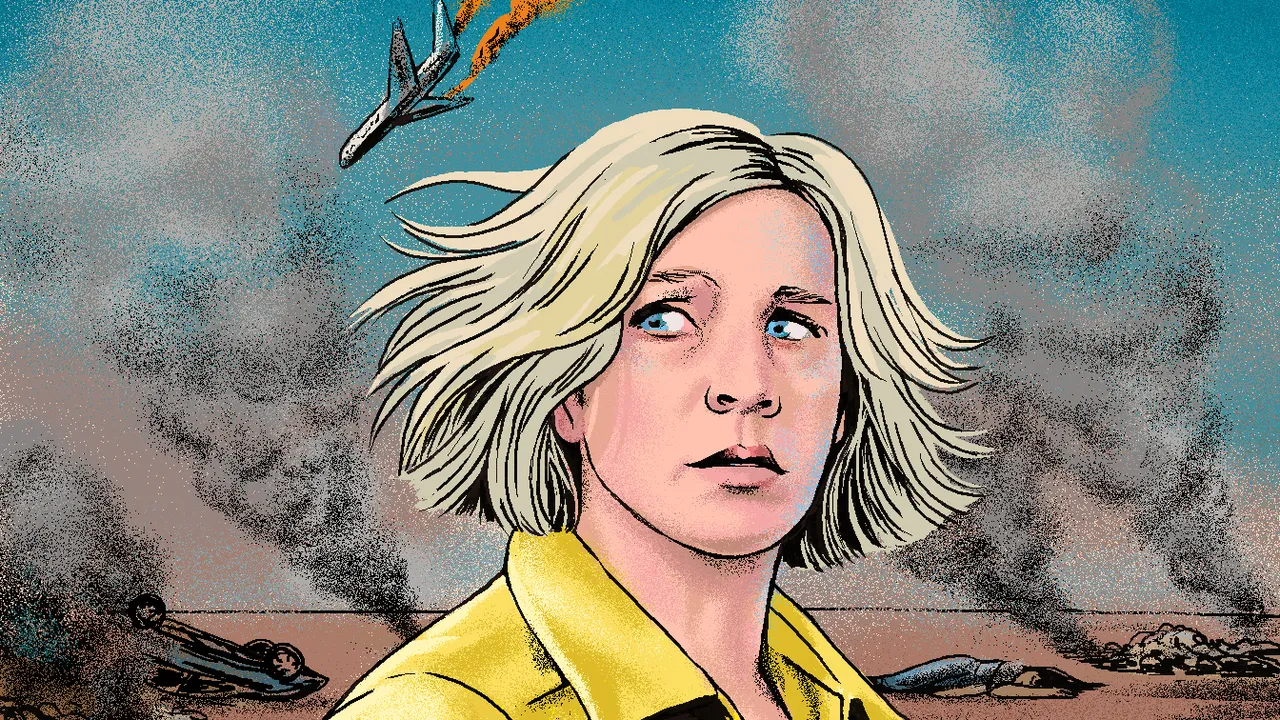

Civilization outlasts humanity in the new sci-fi drama “Pluribus.” On the night that the world as we know it is destroyed, a novelist named Carol Sturka (played by Rhea Seehorn) sees cars and planes veer off course, an emergency room full of convulsing bodies, and her city, Albuquerque, on fire. The President dies under mysterious circumstances, and, more devastatingly for Carol, so does her live-in partner, Helen (Miriam Shor). Then, in less than an hour, the apocalypse cleans up after itself. People stop convulsing. They put out the fires. Granted, they’ve been hijacked by an extraterrestrial virus—but, when they move to retrieve Helen’s body and Carol tearfully protests, they listen. “We just want to help, Carol,” they say, in unison. Not since “The Twilight Zone,” when aliens arrived promising “to serve man,” have the end times come in such obliging fashion.

“Pluribus” is Vince Gilligan’s much anticipated follow-up to “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul,” in which Seehorn co-starred as the straitlaced lawyer Kim Wexler. The new series shares other elements with its predecessors, including the New Mexico backdrop, but for longtime Gilligan fans like myself it feels more like a callback to his first TV job, as a writer and eventual executive producer on the paranormal procedural “The X-Files.” That show, which centered on the F.B.I. agents Mulder and Scully’s investigations of unexplained phenomena, first revealed Gilligan’s preoccupation and playfulness with notions of order and chaos. He made his directorial début with the episode “Je Souhaite,” in which Mulder stumbles upon a genie and dutifully wishes for world peace—only for the smirking spirit to wipe out mankind. “Pluribus” turns on a version of the same trade-off: the destruction of our species, however ruinous for Carol, might just be the best thing for the rest of the planet.

As we learn in Episode 2, nearly a billion people died on the same day Helen did. Those who survived—all except Carol and a dozen others scattered around the globe—have been integrated into a single being, bound by a “psychic glue” that allows unfettered access to the thoughts and memories of the entire collective. When Carol speaks to anyone with the virus, she is technically speaking to pretty much everyone else on Earth. The word “I” approaches extinction, since the mass speaks as a “we.” They differentiate themselves only for her comfort, beginning interactions with a cheerful download on the host she’s addressing: “This individual went by Lawrence J. Kless, or Larry.” Though Carol appears inexplicably immune, they’re amiable and keen to bring her into the fold as soon as they can figure out how. Their Stepford smiles take her back to the last time she was surrounded by upbeat strangers bent on changing her—as a teen-ager at a conversion camp. But her new keepers are welcoming of all sexualities; an uninfected Mauritian man named Koumba (Samba Schutte) notes that racism is also a nonissue. Carol’s reflexive resistance in the face of a peaceful, practically frictionless society becomes the animating principle of the show: What if everyone else’s paradise is your personal hell?

Our Far-Flung Correspondents: A Centenary Issue

Subscribers get full access. Read the issue »

Even before her fellow-humans’ contamination, Carol didn’t seem to have much use for them. She spent her days churning out best-selling romances that she deemed “mindless crap” and harbored a corresponding contempt for her fans, hiding both her queerness and her more serious literary ambitions in a bid for broader appeal. A certified misanthrope, she makes no attempt to check in on friends or family after the initial catastrophe; Helen aside, it’s not clear whether she has any. Most of the other survivors she meets have a loved one or two in tow—though it’s hard to say how close those relatives are to their pre-viral selves—and a surprising openness to the new normal. Carol is assigned a liaison from the hive mind, Zosia (Karolina Wydra), an unfailingly polite and stubbornly uninteresting woman who uses the wealth of information at her disposal to try to mollify her unhappy charge.

In the early episodes, the mass is a potent metaphor for artificial intelligence. It is destructive but solicitous, well informed but dumb as hell. When Carol sarcastically tells Zosia that the only thing that would improve her situation is a grenade in her hand, they have one delivered to her home forthwith. Ever eager to please, they tell Carol that her writing and Shakespeare’s are “equally wonderful.” And they’re just as happy to comply with baser desires. Koumba uses them like a concierge service, commandeering Air Force One to jet-set around the world, waited on all the while by a retinue of babes in leopard print. Zosia says that they don’t mind his sleaze: “For us, affection is always welcome.” Gilligan has said that the show was conceived about a decade ago, before A.I. became a widely adopted consumer technology. Still, the end credits state, pointedly, “This show was made by humans.”

Millions of offscreen casualties aside, it’s clear that Gilligan is aiming for a lighter—and stranger—outing than his two previous series. (For all that “Pluribus” delights in eerie atmospherics, the Southwestern sunniness keeps things from getting too dark.) The uncanny scenarios he conjures are a source of humor, intrigue, and genuine unease. But the show never adds up to more than the sum of its parts. Carol makes for a maddeningly tunnel-visioned protagonist—one with a shocking lack of curiosity about the entity that’s overtaken the Earth, or even about what the infected do all day when they’re not offering to cater to her whims. Her one-note sullenness means that Seehorn, who was heartbreaking as the repressed Kim on “Saul,” is squandered as the lead of her own show. The contentment and coöperativeness of the hive mind are similarly tough to dramatize.

The invaders’ “biological imperative” to absorb everything around them is “Pluribus” ’s chief source of tension: Will Carol, who takes stabs at defiance but has none of the requisite skills, find a cure before she’s subsumed? But the “joining,” as Zosia calls it, could take weeks or even months, and the lack of narrative urgency is intensified by drawn-out sequences of time-consuming toil. In the pilot, Carol struggles to load Helen’s collapsed body onto a truck bed to take her to the hospital; later, it’s another arduous undertaking to dig a hole deep enough to bury her in their back yard. Such displays of trial and error were a revelation on “Breaking Bad,” when Walter White’s flailing sold the challenges that he faced in transforming himself from an unassuming chemistry teacher into a ruthless drug lord. (No one just knows how to get rid of a dead body.) On the new show, Carol, facing down layers of volcanic rock and a likely case of heatstroke, eventually has to accept Zosia’s help with Helen’s burial. The concession should feel significant, not least because Zosia was sent by the collective for her resemblance to the love interest in Carol’s novels: a fantasy to replace the real woman she’d lost. Yet Seehorn and Wydra’s interactions are more stilted than charged.

I’m aware that this is the kind of series we should feel lucky to have at this disheartening juncture in television. One of the medium’s great auteurs has created something wholly original and impressively unpredictable, with the mass gradually revealing vulnerabilities that feel truly unique in science fiction. But its otherworldliness also means that the show has difficulty developing Carol’s relationship with Zosia—or anyone else—in a meaningful way. As the nine-part season chugs along, the entity becomes less of a character than a puzzle to solve. The A.I. analogy gives way to something much less satisfying: a horror story about what their version of living in harmony would really entail. Carol, blinkered though she may be, could have called that from the start. As she grouses at the outset, “Nobody sane is that happy.” ♦